Julia Alexander’s Blog Post is quite long but worth a read, touching on modern culture’s leanings towards binge watching, multiple subscriptions, and how the mind is over wrought by trawling through mountains of content and a meandering internet that is designed to distract. Here we have a description of how the digital world is changing what it means to be human. It brings to mind overtones of ‘technological determinism’– digital devices define and govern how people use them, (Dahlberg 2004), but also ‘community cultures’-the growing social dimensions of virtual worlds and the massive increase in communication and interaction on the web (Knox 2015).

The sheer size and randomness of this communication brings to mind the concept of Cousins (2005) Rhizome, which we learnt about in IDEL. It is reflective of our daily use online as well, very little is remembered when we flit from piece to piece and play youtube videos at twice the speed to save time.

Rhizome, Represented by Galerie Dusseldorf

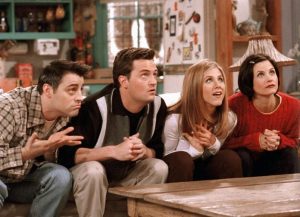

What I liked from Alexander’s piece was the remembrance of mass media monoculture of the 1990’s and how it contrasts with what we have today. In the 90’s, people had to wait for the next episode of their favourite show, most likely together with their peers and at the same time as them. The show was dissected by the groups of pals and co-workers the next day after it aired. It was enjoyable aspect of 90’s culture, a chance to come together and break bread over common interests and comedy.

The TV was the tool that we watched, still separate from the human body. The interaction and dissection was done with physically present peers and not via the technology.

By contrast it is the propensity of modern day culture to view content and chat about it, via personal devices that are completely individualised, which can be physically isolating. The sheer volume of content viewed means less in depth thinking and pondering. Content depends on our demographic, our preferences, and our click history. Youtubers that are incredibly famous across the world are unknown by our friends within the same social circle. Individuals from any background can post something for free on Youtube, TikTok or a myriad of outlets and so there is a low barrier for entry to access our devices.

By contrast it is the propensity of modern day culture to view content and chat about it, via personal devices that are completely individualised, which can be physically isolating. The sheer volume of content viewed means less in depth thinking and pondering. Content depends on our demographic, our preferences, and our click history. Youtubers that are incredibly famous across the world are unknown by our friends within the same social circle. Individuals from any background can post something for free on Youtube, TikTok or a myriad of outlets and so there is a low barrier for entry to access our devices.

I would rather find the hope in this though. Yes we can be physically isolated but our online self will use the internet to find the people that are ‘part of the tribe’ (social determinism) . I would hope that we learn to break down the volume of good and bad content so that we can usefully educate ourselves. Who is to judge what will constitute a ‘useful’ education, when each graduate will need a different preparation and a variety of graduate attributes depending on their life context? But I hope that analytics and more seasoned members of our online tribe will play a part; helping us to filter towards our natural leanings and personal strengths, to tailor our education along individualized trajectories through teeming repositories of art, entertainment and knowledge. The danger of course is who is writing the analytics, but I hope we can overcome that too.

References

Cousins,G, YEAR; Learning from Cyberspace IN Roy Land and Sian Bayne (eds), (2005) Education in cyberspace, London: RoutledgeFalmer. 8, 117

Dahlberg, L (2004). Internet Research Tracings: Towards Non-Reductionist Methodology. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 9/3., as quoted by Knox, J (2015) chapter1. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2004.tb00289.x/full

Knox, J 2015, Critical education and digital cultures. in M Peters (ed.), Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory. Springer, pp. 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-532-7_124-1